Today, we turn to an unexpected source for Italian recipes: the Depression-era Midwest!

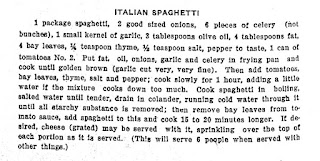

| Italian Spaghetti 1 (8-oz) package corkscrews, shells, butterflies, or any other pasta that goes with a chunky sauce 3 good-sized onions, chopped 9 pieces of celery, chopped 3 cloves of garlic, minced 3 tbsp olive oil 4 tbsp fat 6 bay leaves ½ tsp thyme ¾ tsp salt pepper to taste One (28-oz) can chopped tomatoes, undrained Put fat, olive oil, onions, garlic, and celery in a large pot over high heat and stir until heated through. Reduce heat to low. Cook uncovered until golden, stirring and scraping the bottom of the pot every few minutes. This takes longer than you may think- 45 minutes or so. But you don't need to babysit the pot the whole time- you can just periodically stir it every 5 or so minutes. You don't need to stand over the stove and stir constantly until the last few minutes when they're almost done. Then add the tomatoes, bay leaves, thyme, salt, and pepper. Bring to a simmer and cook slowly 1 hour, adding a little water if the mixture cooks down too much. Towards the end of the simmering time, boil the pasta in salted water until done. Remove the bay leaves from the sauce and mix in the noodles. If desired, grated cheese may be served with it, sprinkling over the top of each portion as it is served. This is very good with a side of sauteed mushrooms. Note: You can caramelize the onions, garlic, and celery ahead of time. They will keep in the refrigerator for a few days. *The original recipe calls for a #2 can of tomatoes, which is 20 ounces. They did not have those at the store, so I purchased the next size up and rescaled the rest of the ingredients.

Source: A Book of Selected Recipes, Mrs. George O. Thurn, 1934

|

|

| A Book of Selected Recipes, Mrs. George O Thurn, 1934 |

Mrs. George O. Thurn included this recipe in the vegetable chapter between "Corn Pudding" and "Escalloped Cabbage." This suggests that Italian recipes had already become normal outside of the Italian neighborhoods in New York. Seeing an Italian recipe in Midwestern cooking handout goes against the popular story among food historians that Italian food was too weird and too foreign for Americans before WWII soldiers returned from Italy. (But then again, food historians try to prove that everything in America originates from Manhattan.)

So, let's get this out of the way before we even start chopping vegetables. Boiling your already-cooked spaghetti for another 15-20 minutes will yield a pot of mush. Maybe people in Depression-era Ohio had to make do with massive German or Scandinavian noodles that need half an hour to cook. (Are German noodles like that?)

I will be nice and assume Mrs. George O Thurn didn't really believe that spaghetti should be boiled into mush. So, let's pretend that people in the area had to make spaghetti with Teutonic mega-noodles because that's all they had in the region. Aside from the part where you boil the spaghetti into a porridge, this looks like a modern(ish) tomato sauce recipe. Mrs. George O Thurn even adds olive oil to the pot.Although we note that she uses no oregano. These days (in America at least), it's not truly Italian if it doesn't contain oregano.

We begin with a bit of a recipe error. For whatever reason, I thought Mrs. George O. Thurn had us cooking the onions in bacon fat. Cooking dinner in the drippings from that morning's breakfast certainly seems like a good choice for the middle of the Depression. But Mrs. George O. Thurn simply tells us to use "four tablespoons fat." Since we cooked bacon recently, we figured that the leftover drippings might make dinner a little bit more flavorful. (You couldn't taste the difference, but at least we economized!)

Frozen vegetables weren't a thing in the 1930s, but I think Mrs. George O. Thurn would have approved. She was really big on saving time by modernizing. If you simply dump a bag of frozen onions into the pot instead of chopping fresh ones for yourself, this is all the knife-work you have to bother with.

Of course, after we saved time by not chopping the onions, we then had to give them over an hour to cook. Recently, I read an article about how you can't caramelize onions in five minutes. After spending all my cooking life blaming myself that I never could get the onions "golden brown" in less time than it takes to steep a pot of tea, it was so blissfully liberating to learn that you really need at least half an hour to cook onions without burning them. I don't think it's quite the correct word choice to say I felt vindicated, but I certainly felt something. I didn't mind the long cooking time since I merely had to give the pan a quick stir every now and then. I didn't even bother staying in the kitchen until the vegetables were nearly done.

|

| The onions and celery may have ended up cooking for over an hour, but I only spent ten minutes fussing over them. |

However, the long cooking time meant a very late supper. For all the times I've read this recipe and wondered if Midwestern spaghetti was any good, I didn't see the extremely long cooking time. I had to apologize to everyone and tell them that the "quick supper" required over two hours on top of the stove. To Mrs. George O. Thurn's credit, this recipe demands a lot of the pot's time but asks very little of yours.

I blame Mrs. George O. Thurn for the bay leaves. At least she doesn't subscribe to the myth that you drop one lonely leaf into a huge pot of simmering supper. But since we had to purchase the things, I can join the legions of people who have a canister of bay leaves on the back of the shelf slowly gathering dust. It also meant I had to find all of them and fish them out of the pot later on. It turns out that bay leaves make cooking just ever so slightly more annoying. You have to stir your pot very carefully lest you break one of them- or else you'll later be hunting down little leaf-shards with a slotted spoon.

I got out the big spaghetti pot to make this, but that was an oversized mistake. While we in this millennium are used to serving spaghetti as a one-pot meal, let's go back to the 1930s and look at the last sentence of Mrs. George O. Thurn's directions: "This will serve six people when served with other things." Those last five words should have gotten a lot more emphasis, because this tiny pot of spaghetti is not going to serve six people on its own. No amount of ranting about increased portion sizes over the past several decades will make up for the small yield of spaghetti. Apparently people in the 1930s didn't put a single steaming pot on the table and declare that dinner was served.

As aforesaid, we pretended we never saw Mrs. George O. Thurn's instructions to boil the spaghetti until quite dead. Instead, we dumped the cooked noodles into the sauce and declared it done. This wasn't really a "sauce." Mrs. George O. Thurn gave us more of a hot pasta salad than the spaghetti-with-jarred-sauce that we know today.

It tasted like we tossed spaghetti with fresh vegetables, but with more effort into making it come out nice. You wouldn't think boiling canned tomatoes for an hour would do that, but a surprise is a surprise. The celery, despite cooking for two hours, was still crunchy. I would definitely recommend this as for the summertime, with some sauteed mushrooms on the side. Even the two-hour cooking time won't heat up the kitchen as much as you might think. The stove burner is set to low the whole time. Things really only get hot and steamy when it's time to boil the noodles. And this spaghetti tastes very light and summery. Whether Mrs. George O. Thurn's spaghetti is Italian or not, it is very good.