Which brings us to mixing a cake! Did you know how many fascinating physics are happening in your mixing bowl (all of which I had to memorize for a test)? Did you know how many ways there are to mix the a cake? Multiple methods were mentioned in class (there are practically as many different ways to mix a cake as there are cake recipes floating around online), but we in class only looked at a four.

"It makes such a difference!" the teacher insisted. "If you don't believe me, go home and try them all at on the same recipe!"

We at A Book of Cookrye were very skeptical indeed. How much difference can it make unless you do something wrong like overbeat it until the flour toughens up everything? Therefore, because it involved a lot of cake and also a lot of experimenting, we were more than willing to test this.

However, if you're going to try four cake-mixing methods, you will end up with four cakes. As we no longer live in a dorm with people to give baked goods away to, what would we do with four cakes? We then got invited to a friend's house party. Which brings us to today's recipe:

|

| Source: All Electric-Mix Recipes Prepared Specially for your Dormeyer Mixer, 1946 |

We've run this recipe before. Since know how it comes out when you make it as the directions tell you to, it seemed as good a choice as any. Also, it tastes good, so the prospect of having four of them threatening the counterspace and my recently-successful dieting isn't at all dreadful.

Well, let's start the method trials with...

THE CREAMING METHOD

|

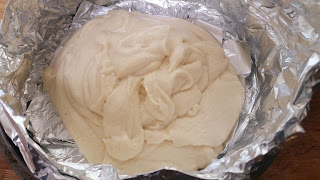

| Notice the foil condom on the pan because we have a lot of cakes coming up and no dishwasher. |

This one comes up the most often in cake recipes. You know, the recipes where the directions read something like "Cream butter and sugar, then beat in the eggs. When all is mixed, alternately add the flour and milk, beating just until mixed..."

We started to see compelling evidence that changing the mixing method would make a lot more of a difference than we suspected. The batter was a lot thicker than when we made it using the original recipe directions, which looked like this:

Not that the original recipe is watery-thin, but changing the mixing directions made a batter that almost did not want to spread into the pan.

While that was baking, we proceeded to...

THE FLOUR-BATTER METHOD

Apparently this produces a really good pound cake. What you basically do is mix the butter with half the flour. Then you beat the eggs and sugar until they're good and foamy, and then put the whole thing together. In class, they admitted that "This way is really old-fashioned, you don't really see it anymore." Old-fashioned? Rarely used? Of course we're going to try it!

As you can see, while the creaming-method batter was already thicker than the original recipe, this made a little mountain in the pan.

When you make the same cake over and over again in one day, you eventually stop needing to look at the recipe. If I had a dishwasher, I might have measured out all the ingredients for each cake ahead of time because I got really tired of having to do it repeatedly. But who wants to hand-wash all those storage tubs? Well, let's move right on ahead to...

THE MERINGUE-BATTER METHOD

We've actually posted a cake made like this before. Basically, you mix the flour and the butter together until it looks like you're making a pie crust. Then you add the egg yolks (if the recipe uses whole eggs), forcing them to mix into the crumbly stuff in the bowl. After that, you make a meringue out of the egg whites and the sugar, and mix that into your flour clods. Congratulations! You have a cake!

Well, that method was a lot of fuss and bother. And after having to get out so many bowls for separately beating eggs, separately combining some of the ingredients before adding them to something else, and so on, I asked myself, "Can we do this with less dishes?"

It turns out, we can! Let's move on to the one I really was looking forward to...

THE FUCK-IT METHOD

Put everything in the bowl and insert an electric mixer. If you hate having to make an effort, this will feel great.

They gave this method a nicer-sounding name in class, but I'd rather call it for what you're probably saying as you dump everything in.

We were warned that this is not the best method for cake mixing and that you have less control over the batter. The phrase "improper incorporation of air cells" was deployed. But how much difference could it really make?

|

| I don't know where that metal plate came from, but I was very glad to find it when I looked in the oven and saw that the fuck-it cake was dripping all over the oven. |

Apparently it makes a lot of difference.

|

| Incidentally: note the planning ahead in moving the cake that was already in there to the front when adding the next one since it would theoretically come out of the oven first. |

After hastily jamming the aforementioned metal plate under it, we intended to finish baking it just to see what would happen. However, it kept gushing out of the pan. You'd think eventually there'd be no more batter to spill out, but this kept oozing over, dripping out astonishingly foamy splurts.

It turns out that cake batter makes an incredibly strong adhesive, seeping under the foil to glue it to the pan, and then gluing the pan to the plate that was supposed to catch the batter drippings. You could hold it upside-down and nothing fell.

Well, let's have a look at the three survivors.

The meringue cake had this ever-so-slightly shiny top crust, the flour-batter cake was really spongy and was most likely to bend with the foil when you pulled it out of the pan rather than hold its shape, and the creaming-method cake looks... like cake.

You can really see the top crust of the meringue-cake here. It looks kind of like that top layer you get on brownies.

Before taking these cakes out in public, we decided to spend about 45 seconds stirring together a big batch of cinnamon icing, which we then dumped on all three.

And so, I brought all three cakes to my friend's house party.

Incidentally, the really great thing about lining the pans with foil (aside from not having to wash them) is that once you've arrived to wherever you were going and set the cakes down on the table, you can lift them out of the pans, stash the pans in your car, and not have to worry about forgetting them or anyone scratching them.

But what did everyone think of these? After explaining what was on trial here, I asked my friends what they thought of the cakes. Could they tell the difference? Why, yes they could!

There wasn't much difference in taste, but as the group photo of uniced cakes suggests, they had very different textures. While everyone liked all of them, the creaming-method cake was least popular (though substantial portions of all three disappeared from the pans). The flour-batter cake was slightly drier than the creamed cake, but also lighter. The meringue-batter cake was the most popular, if we measure popularity by how much cake was missing from the pan afterward.

To my own surprise, it appears that not only does changing how you mix a cake give you a different texture, it can actually change the taste. No one specifically noted a flavor difference in the cakes, but a lot of people thought I had put sweeter icing on the flour-batter cake. Since the icing on all three was from the same big batch, that must mean the cake underneath it tasted different.

And so, I am very glad I had kept my skeptical pooh-poohing to myself in class. It turns out the teacher was right.