This recipe hooked me with the first sentence.

|

| Woman's Club of Fort Worth Cook Book, 1928 |

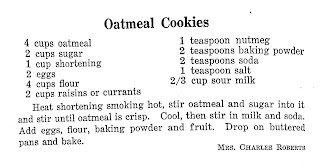

| Oatmeal Cookies 2 cups oatmeal 1 cup sugar ½ cup shortening ⅓ cup sour cream 1 tsp baking powder 1 tsp baking soda ½ tsp salt ½ tsp nutmeg 1 egg 2 cups flour 1 cup raisins or dried currants In a large saucepan, heat shortening until smoking hot. Add oatmeal and sugar to the pot, and stir until oatmeal is golden and crisp. Be very careful to thoroughly scrape the bottom of the pot while you're cooking. Set the oatmeal aside to cool completely. When the oatmeal is at room temperature, heat oven to 350°. Have your cookie sheets greased and ready. Add the milk, baking soda, baking powder, salt, and nutmeg to the pot. Mix well. Then add the egg, and mix well again. Mix in the flour and the raisins. Drop onto the pans. If you want them a little more neatly shaped, spritz them with cooking spray and gently pat them flat. Bake until golden on the bottom, about 10-12 minutes.

Mrs. Charles Roberts, Woman's Club of Fort Worth Cook Book, 1928

|

Are we... are we frying the oatmeal? I showed this to everyone else, and they were as mystified as me. We had to give it a go.

Apparently some people swear that shortening is better for frying than anything else. But I could never bring myself to fry anything in melted Crisco. I kept imagining the shortening resolidifying in the food, impregnating it with slick white grease.

My misgivings aside, we got the shortening hot enough to make French fries, and then it was time to dump in the oatmeal.

I had imagined the oatmeal floating in the boiling fat like a batch of Tater Tots. But instead, the oatmeal sucked up the shortening like an extra-thirsty sponge. Anyone trying this should know that you need to be very diligent with your spoon-work because this will really want to burn onto the bottom of the pan.

Getting back to Mrs. Charles Roberts' directions, how was I supposed to tell whether I had gotten this cooked "until crisp?" It's not like I could taste-test the oatmeal when it was searing hot. And I couldn't set a little on a plate to cool off for a bit. That would require briefly leaving the pot alone, and if I stopped stirring the contents of the pot for even half a second, the oatmeal would burn. I eventually decided that the oatmeal was now granola-colored and therefore probably good enough. It was also making gravelly crunching sounds against the sides of the pot.

It looks like innocent oatmeal, but keep in mind that it is impregnated with shortening. See how the bottom of the pot is completely dry? The shortening didn't all float away, it's in the oatmeal.

|

| I didn't realize how dark I had toasted the oatmeal until I compared it to a spoonful out of the canister. |

At this point, we are directed to cool off our scorching-hot granola. At first I thought I would speed things up by immersing the whole pot into a big pan of cold water. The oatmeal promptly welded itself to the bottom of the saucepan. I had to carefully set the pot back over a low burner so that the shortening would re-melt and let go of the pot. So if anyone is making these, don't bother using a cold-water bath to cool your "Criscoatmeal" off faster. Let it cool off in its own good time.

As we added the next few ingredients, I was waiting for everything in the pot to start looking like a cookie recipe in progress. So far, it looked like future trash. However, this recipe has the submitter's name under it. Therefore, I reasoned, it must work. Otherwise Mrs. Charles Roberts would have to endure years of people passive-aggressively saying "So I tried your cookie recipe..." while chitchatting at the woman's club meetings.

After we started stirring everything together, I noticed that I'd forgotten to add the nutmeg. I don't blame myself for that since Mrs. Charles Roberts forgot to mention it in the directions.

I actually find this kind of error delightful. When you hold a copy of The Woman's Club of Fort Worth Cook Book, you can tell that they paid extra to have it professionally typeset and then printed on the good paper. It's even a proper case-bound hardcover instead of something more budget-friendly like spiral-binding. But even though the clubwomen spared no expense at the printshop and bindery, their recipes still have the same sort of little mistakes that one finds in cookbooks typed up by volunteers and then printed on the nearest mimeograph.

Speaking of little recipe mistakes, it looked like we were making one. As the mixture in the pot kept worsening, I started to think that Mrs. Charles Roberts hadn't cooked since her pre-debutante days. Perhaps she got the recipe from the household help, and then made some transcription errors while writing it out to send to the Cookbook Committee (always capitalized).

Here is the, um, cookie dough after we had everything in there but the flour and the raisins. I was extremely glad I didn't halve this recipe but instead quartered it. I didn't see how this slimy, greasy oatmeal was supposed to turn into cookies.

To my surprise, the flour actually turned this mess into recognizable cookie dough. Keep in mind that it took a lot of persistence to force the last little crumbly flour-bits to actually mix in.

And here, at last, are the raisins. I love how Mrs. Charles Roberts calls the raisins "and fruit" in the directions. I know it's because she listed "raisins or currants" in the ingredient list, but I find it charmingly quaint all the same.

The raisins technically mixed in, but they kept falling out whenever you lifted out a spoonful of this very dry dough. This did not bode well for the part where we're supposed to "drop onto buttered pans and bake."

We dropped the cookies onto the pan as directed. They went into the oven looking like clumps, and came out of the oven unchanged.

A lot of cookies have a homemade charm when they come out of the oven in the same shape as when they dropped onto the pan. But oatmeal-raisin cookies don't look like the cute-aprons-and-checked-tablecloth kind of homemade look to them. They are the kind of homemade that comes with apologetic mumbling of "This is my first attempt."

|

| As the joke goes, "If you like them, the recipe's been in the family for years. If they're bad, I found it on Pinterest." |

I've had a lot of lumpy drop cookies when using recipes of this time period. I therefore have to wonder if people in the early 20th century liked their cookies to look like someone just dropped dough lumps onto the baking sheet, or if the instruction to "drop onto pans and bake" carries a lot of implied cookie-shaping directions that no were too self-evident to write down. You know recipes never say something like "Crack open the eggs, save the interior contents, and discard the shells"? Maybe cooks at the time implicitly knew that you were supposed to shape your drop cookies a bit before baking them.

It will never stop amusing me that raisins in cookies puff up exactly when the cookies are ready to take out of the oven. When the cookies look covered in beetles, they're ready to remove!

These cookies tasted a lot like we stirred in granola instead of oatmeal- which makes sense given that we basically made a batch of the stuff and then encased it in dough. They were really crunchy in a way no oatmeal cookie ever is. While we were trying them, someone else said "Hmm." After a lot of careful thought, he said "These are more like oatmeal biscuits than cookies."

The cookies ended up a little harder than I would have liked, but they were surprisingly flavorful. Maybe impregnating oatmeal with shortening is a better choice than I thought. But while the cookies use the same amount of shortening as any other recipe might, making it hide in the oat flakes doesn't sit right with me.

But with that said, these were unexpectedly addictive. We couldn't stop eating them. I was even asked to make them again. If I can get over my shortening-related misgivings, I just might.

.jpeg)

.JPEG)