Today, for the Historical Food Fortnightly, we at A Book of Cookrye are looking at modernized versions of the food of yore!

Anyone who's interested in the Fortnightly will now be a bit annoyed at this. The whole point is to make things as close as possible to the original time, right? But even in days of yore, people longed to taste the food from days of even further yore. Recipes with "Old-Fashioned" or "Grandmother's" or similar in their names have been around since well before today's old-fashioned foods were daring innovations. And so, we at A Book of Cookrye found this.

This fortnight's challenge is fruit. We're actually kind of surprised that the fruit challenge is this early in the spring rather than later in summer when all the fruits are in season. But, since fruits are scheduled for this fortnight, we are making this!

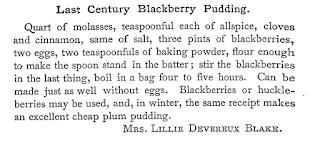

Last Century Blackberry Pudding*

2 c molasses

½ tsp allspice

½ tsp cinnamon

½ tsp cloves

½ tsp salt

1 tsp baking powder

1 egg (can be omitted)

Flour

1½ pints blackberries

Set a very large pot of water to boil.

Mix the molasses, spices, salt, and baking powder. Beat in the egg. Add flour until your stirring spoon will stand up in the bowl. Lastly, stir in the blackberries.

Now you get to boil it in a pudding bag†. You'll need a good-sized cloth that has no synthetic fiber in it (do you want melted plastic in your pudding?). You'll also need a lot of open counterspace. Wet the cloth in boiling water, wring out any excess, and scatter and rub in flour all over it before it cools off. Take the pudding and mound it in the center. Tie the rag around the pudding (you can knot the cloth or use string), putting a lump of flour where you close it. Leave room in the bag for the pudding to expand.

Put the pudding in the pot. The water should completely immerse it. Make sure the pudding doesn't rest on the bottom of the pot or else it might burn. Some people attach a hook to it to suspend it in the water, others put an upside-down pan or something similar under it to make a little platform for it. When the water returns to a boil, reduce the heat to a simmer, keeping it just hot enough to gently boil.

Boil for 2-3 hours.

When it's done, take it up, set it on a plate, and let it sit out for a few minutes unopened. Then open the cloth, lay whatever plate you plan to serve it in on top of the pudding, get a good grip on the whole thing, and flip it over. Take off the cloth and it's ready.

*For the sake of record, this recipe is halved from the original.

†Or you can forget about period-correctness and use a small tube pan instead. Grease it before putting in the pudding and have something in the pot to keep the pan from touching the bottom. The water should come halfway up the sides.

|

These days, especially since so many old books are getting digitized, it's so easy to compare a recipe from a recent cookbook for Old-Fashioned Whatever to recipes from when Whatever was new. And of course, you'll see the ingredients and the directions changed to adapt to current tastes- or updated simply because in order to do the original, one would have to find now-obscure kitchen implements in the back corners of antique shops.

I mistakenly thought this cookbook was from the 1920's, and that the "Last Century" in the recipe name referred to the 1800's. But when I checked the date, I found that we're actually looking at someone in the late 1800's looking back at recipes from the 1700's. Someone from when electricity was just beginning to move from science experiments to public use is looking back to when most Americans had been born British subjects and kitchens had fireplaces with kettles hanging over them instead of stoves.

|

| When you have to pour out a whole pint of the stuff, you find the existence of the expression "as slow as molasses" justified. |

Since one can nowadays look up recipes from when puddings like this weren't yet considered old-fashioned, it's interesting to compare what's changed in the recipe since before it became old-fashioned and what stayed the same. Since Mrs. Devereux Blake just says "boil in a bag 4 to 5 hours," it looks like English-style boiled puddings still appeared a lot on American tables and women still knew how to make them. Otherwise, the recipe would have had a paragraph or two detailing just how to use a pudding bag instead of just directing that you use one.

The most obvious change: There's no fat in this at all. Puddings like this used to have an ungodly amount of fat (usually beef suet) added. People who make recipes truer to the original than this one inevitably mention the fat coating the inside of their mouths when they eat it. I was glad to see it omitted because it meant I didn't have to track down someone who still sells the stuff.

Now, one might think that maybe by the 1880's, suet was already getting hard to come by. But if that were the reason for taking suet out of the recipe, Mrs. Lillie Devereux Blake would have put in a substitute (people usually use butter and mutter how it's not the same but it's the closest you'll get). Instead, she just took it right out of the recipe altogether. Maybe people in the 1880's were starting to get suspicious of such gratuitously fatty cooking (after all, a lot more people lived in the city and therefore didn't spend all day doing farm work). Or maybe using gratuitous amounts of suet (or a substitute) was considered too passé- even for a recipe billed as being old-fashioned.

|

| If you don't like molasses, this recipe may not be for you. |

The other recipe change, visible at about 12:30 in the above picture, is baking powder. While

the first cookbook written in America is also the first to use what would later evolve into baking powder, the refined wood ash and other things people were using in the time period this recipe tries to emulate either didn't work reliably or left unnerving aftertastes. Since puddings like this involve such a long time working on them (usually), I doubt anyone in the 1700's would have risked all that time and ingredients on a baking powder failure.

|

| I just thought this looked pretty. |

Actually, this recipe was going pretty well. I'd always thought one of the reasons boiled puddings went out of style was that they were

so hard to make. We were just dumping things into a bowl and stirring. Aside from waiting for all the molasses to pour out of the bottle, all we did was dump things into a bowl and stir. Before we knew it, the spoon was standing up.

...or, nearly so. We realized we'd forgotten one thing:

Granted, the recipe says we don't

really need eggs, but we're already well out of familiar territory in making this. Even if Mrs. Lillie Devereux Blake who contributed this recipe says it'll work without them, we didn't want to risk serving up a boiled lump of molasses-flour paste.

All right, we've only got one more thing to add here:

|

| Yes, they're frozen. It's not period-correct, but have you seen the price of fresh blackberries this time of year? |

And this brings us to the last thing changed in the recipe. Puddings like this usually call for five or six different kinds of dried and candied fruits, as well as multiple kinds of nuts. Nope, we're just using one type of fruit, and it's neither candied nor dried.

|

| This may pass for pudding in England, but this is America. |

At this point, we were pleasantly surprised at how easy this recipe was.

All we had to do was dump things into a bowl and stir them together.

In a way, it was kind of a bummer because it mean that not fifteen

minutes after starting this endeavor, we had to bring out our pudding

cloth. But what could we use? We don't have any large rags around the

house. We refused to go to a fabric store and buy cloth for something

we're not likely to make again. We needed something made of all-natural

fibers so it wouldn't melt in cooking. Something big enough to wrap

around an entire... whatever this thing was.

|

| Hopefully we don't dye the pudding blue. |

The irony of making a pudding in a shirt that says I BEAT ANOREXIA BUT I LOST 30 POUNDS FIRST is not lost on me.

|

| Be sure you don't use a shirt with silkscreening on it- you might end up with melted plastic in your pudding. |

All right, we've got us a pudding. Let's just... oh God. Am I really doing this?

You know, the idea of cooking things in a cloth sack doesn't bother me. What I

really don't get is how this isn't going to be a waterlogged mess when it's allegedly done. It's claimed that if you wet it with boiling water and coat it before it has time to cool down, water won't get in and ruin it. I've got no idea if that's true, but I do know my love of very long, scalding-hot showers finally paid off when I had to wring out a shirt dipped in boiling water and then smear flour all over it.

A final cooking tip: Either get one of those pots that is more of a galvanized bucket with handles (go to the nearest Mexican grocery and ask for a

tamale pot), or give up and just put a bucket right on the stove, or be sure no one in the kitchen minds that no matter what you do, the water will spill over the rim every few minutes. Given how much the pot boiled over (even though we had the burner nearly as low as it went), we had no idea how the waterline remained right at the rim. We then noticed that the pudding had outgrown the pot.

To anyone who thinks we should have pushed the lid back into place: We tried. Whatever sort of pudding thing this is, it resisted getting downsized unnervingly well.

On the bright side, once it was in the pot, it really didn't need any more fussing from us. Yes, the cooking time is multiple hours, but we didn't have to do any basting, stirring, or anything else. Once we put some rags in the path of the water boiling out of the pot to absorb it before it got everywhere, we could just leave it and mind our own business until it was done. Seriously, once it was on the stove, it was like a Crock-Pot. We just ignored it. Heck, if you had a lot of things to make on the stovetop, you could just set this on the back burner, ignore it, and it will be fine while you do everything else.

When eventually the alleged pudding was done (or so we hoped- we had no idea how we're supposed to tell), we lifted it out of the pot.

Uh... well... at least it looks like those old British Christmas specials they air on PBS- so it must be going right. But in those shows, they typically remove it from the rag. Eager to see how this thing qualified as a pudding, we unfurled the shirt to reveal...

We'll let Ethel Mertz speak on our behalf.

They never look like that on those TV shows. Those British people in their 70's clothes don't bring in a poopy flower, they bring in this ball-shaped thing with a random piece of plant stuck in the top! It became ever more apparent that we had to somehow take this fragile, scalding-hot thing we had just made and turn it over without letting it fall apart and without giving ourselves some historic burns in the name of historic food. We clapped a plate onto it, flipped it over, and hoped for the best.

|

| Well, at least we can get the rag out from under it now. |

At this point we had uncertainty. Since we weren't going to serve it immediately, were we supposed to leave it under a wet rag until we were ready? Or would our friends come over and realize they were about to eat out of one of our shirts?

|

| I think some of the blue dye got on the pudding. |

So, eager to cut this thing open, we found... it's a cake.

As for the results: Everyone who tried this thing liked it. Seriously. I'm very surprised. It tastes like a spice cake. I was expecting something really soggy and tasting like cotton since it spent the entire time bagged up in it. I asked my (camera-shy) friends who came over to try it with me what they thought.

First person's answer: "It's good." He stopped there because he was too busy eating it.

Second person's answer: "It's interesting, taste-wise. Kind of like a cross between cake and pudding."

There was only one problem with this recipe, really. We'd invited five people over to try this. The randomly-placed obligations of adulthood being what they are, only two could make it. So, despite cutting this recipe in half, there were a

lot of leftovers which were unnervingly getting darker on the plate.

However, this thing

refused to go stale. It went the other way somehow- the center went runny (well, goopy) after a few days. The leftovers aren't so bad, though this has got to be one of the heaviest desserts ever featured on A Book of Cookrye. Unless you're making this for a

lot of people, expect it to be with you for a while.

All right, here's our Historical Food Fortnightly homework!

The Recipe: Last Century Blackberry Pudding

The Date/Year and Region: 1886, America. Since the book has a

list of all who contributed a recipe and where she's from, this specific recipe comes from New York City.

How Did You Make It: Dump molasses and spices into a bowl, stir. Add lots of flour, stir. Add an egg, stir. Add blackberries, stir. Somehow get it into a T-shirt dragged into service as a pudding bag. Boil and hope for the best.

Time to Complete: About 20 minutes of prep, followed by 3 hours of leaving it on the stove.

Total Cost: About $15ish.

How Successful Was It? A lot better than I thought! It was really good. It looked weird and wasn't like any pudding I've ever had, but everyone who tried it liked it.

How Accurate Is It? Pretty accurate. However, in the name of not spending nearly $10 on blackberries, we got frozen instead of fresh. It may be that the berries were supposed to break up as you stirred them into the really stiff pudding mixture, which obviously didn't happen since they were still frozen solid. Also, I did cut the recipe in half, but since people have been halving and doubling recipes since forever I don't think that counts as a mark against period accuracy.